The earlier days of my design career were not as a UX/UI designer, but rather as an illustrator, which is something I did for around 7 years that shaped my perspective on how to communicate with clients, manage projects, and develop my visual work. With the passage of the years, things started to drift in my head a little bit. I felt the curiosity to try new areas of design that required more complex thinking and were related to solving more substantial problems without relying solely on the subjectivity of my artistic vision, and that's how I started transitioning my career into UX and digital product design.

However, a couple of years after transitioning to my new realm, even though I was doing quite well in terms of visual design execution and, somehow, problem-solving, I noticed that there was something in my skillset that was not aligning completely with my new 'UX Designer' title just yet, but I couldn't sort it out completely.

It was until a few weeks before the COVID lockdown that I came across the 'Business Thinking for Designers' ebook by Ryan Rumsey, and it sparked in my head the missing piece in my skillset that I was not able to detect before: I was lacking business knowledge and understanding.

I found out that due to my more artistic background, I was used to managing my design work in a way that was not often the most efficient in a business environment, which often made me have difficult times quantifying design impact, struggle to manage communication with stakeholders, and overall limited my understanding of business constraints, which was very frustrating.

Even though Rumsey's ebook opened my mind immensely about business concepts beyond simple 'conversion rates' like competitive advantage, trade-offs, market forces, business models, feasibility, differentiation and more, I ended up craving more business knowledge in order to fulfill my desire to become a designer that not only 'designs beautiful things' but also a designer who 'designs things that build impact'. My journey into the world of business wouldn't stop there; it was just the beginning.

The Crazy Decision of Enrolling in an MBA

A couple of years later, in 2023, with that curiosity still present, I took the decision to enroll myself in an MBA at University of Chile (a program fully in Spanish), one of the most prestigious business schools in Latin America, and relocate to Chile... and to be honest, I was terrified.

Even though I already had plenty of years in the corporate world and had already read several books about business and marketing by that time, in the end, I was still a designer who had almost no idea about stuff like finance and economics, so the impostor syndrome got to me for the first months in the program.

It was exhausting, having to work remotely while enrolling in a demanding degree that covers many subjects completely outside your expertise and background, but as time went by, I started to flow with it, to get more familiar with the numbers, with the concepts, and with my new friends at the MBA who supported me to make this personal challenge less harsh. Also, finding out that it's not completely uncommon that some well-seasoned designers in the industry opt for pursuing an MBA degree to polish their career paths inspired me even more to keep pushing in this direction, like the case of Jason Barron, an American designer who did an MBA and published a wonderful book summarizing all the content of the degree with hand-drawn illustrations (highly recommended book, by the way!).

What to Expect in an MBA as a Designer?

An MBA can be broad and cover many subjects that in some cases will have little or no connection with a designer's duties, and it might take a lot of courage for us to get out of our comfort zones and open our minds to different areas of knowledge that sometimes can even clash with the creative side of our brains.

However, there are certain subjects and courses that I believe have brought me the most value for my design career. Some of them include: Entrepreneurship, Digital Marketing Strategies, Business Strategy, Operations Management, and very importantly, People Management.

Having formal training in these areas has been extremely helpful for me to connect the dots in my design career, but if you're a designer who also enrolls in an MBA program, you will probably find other topics more useful, so it depends on your needs, your expertise, and your career path objectives.

Of course, an MBA is not a design-oriented program, so you must be aware that part of the dynamic will be to maintain your design perspective and figure out ways to apply all the different business frameworks to design, and adapt yourself to business thinking rather than a merely creative one, but that's something that will only come with practice.

Key MBA Takeaways for Designers

There's way too much of MBA subjects to summarize in a single article, but here I just want to quickly highlight a few of the subjects that I believe can be useful for designers who want to improve their efficiency and skills within the design industry, so you can research on your own if any of these subjects catch your attention the most:

Financial Literacy

- Budget Management: Especially when working freelance, being able to proactively identify, organize, and track expenses and costs for a design project can be a key driver of success for you and your client. Whether it's software licensing, digital resources, or people management, all designers must be able to manage budgets, at least at a basic level.

- ROI Calculation: It's important to be able to calculate how much the return of a design initiative will be over the actual investment in that initiative. For instance: a design or prototype that is too complex can take more development hours than initially planned, making the overall project more expensive for your client (and probably for yourself since you'll have to spend more time tweaking it back to make it more feasible for them later on). If you can calculate this development time in advance based on an initial design idea, you can reduce a lot of pain for you and your team.

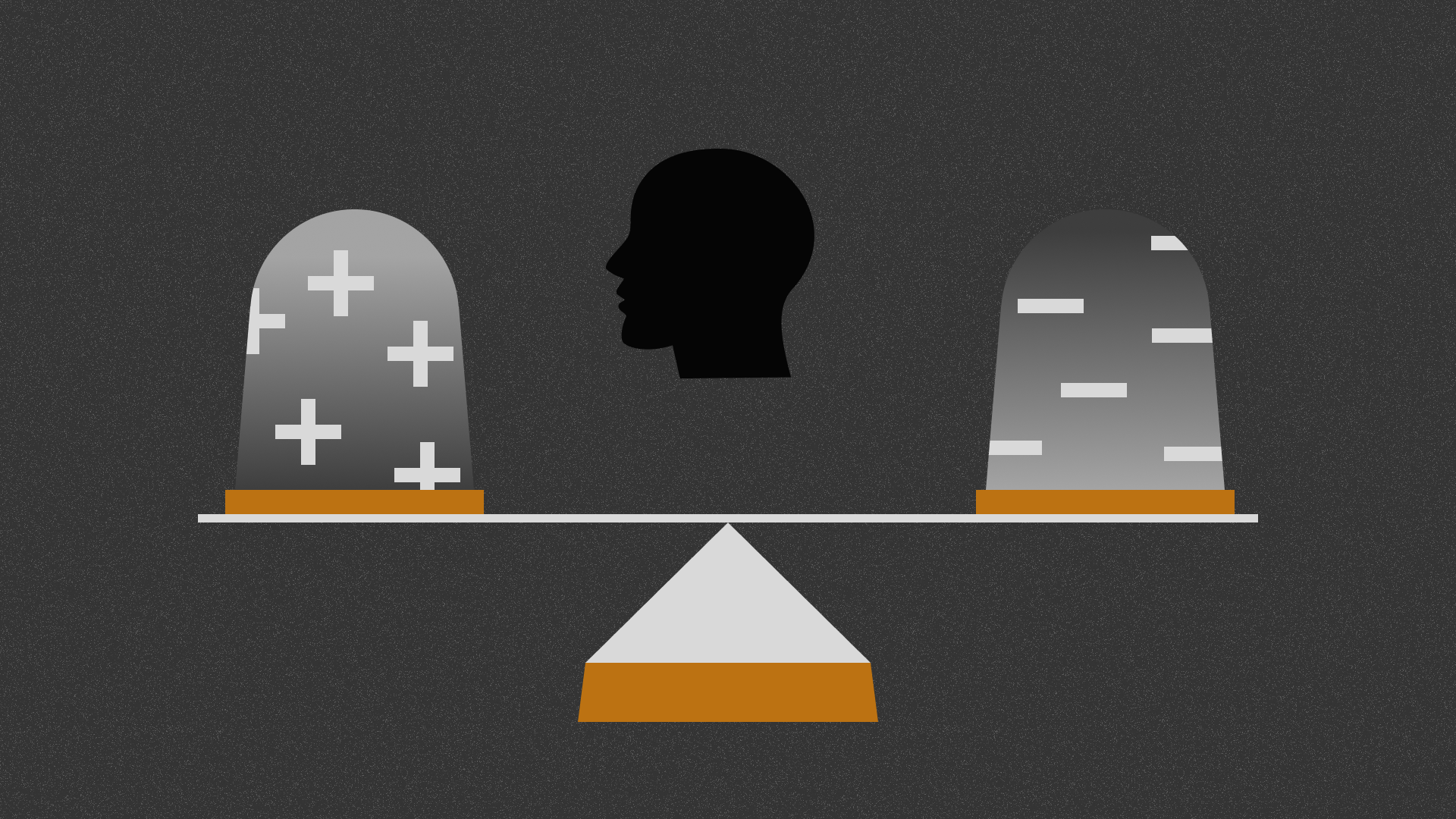

- Cost-Benefit Analysis: Being able to balance the cost vs. the benefit in the different design decisions that we have to make. For example: Do you really need that 'Night mode' version in this app that you're building? Or is it just because it's a trending pattern? Have you estimated how many development hours that is going to take and how much real impact it will have on your users?

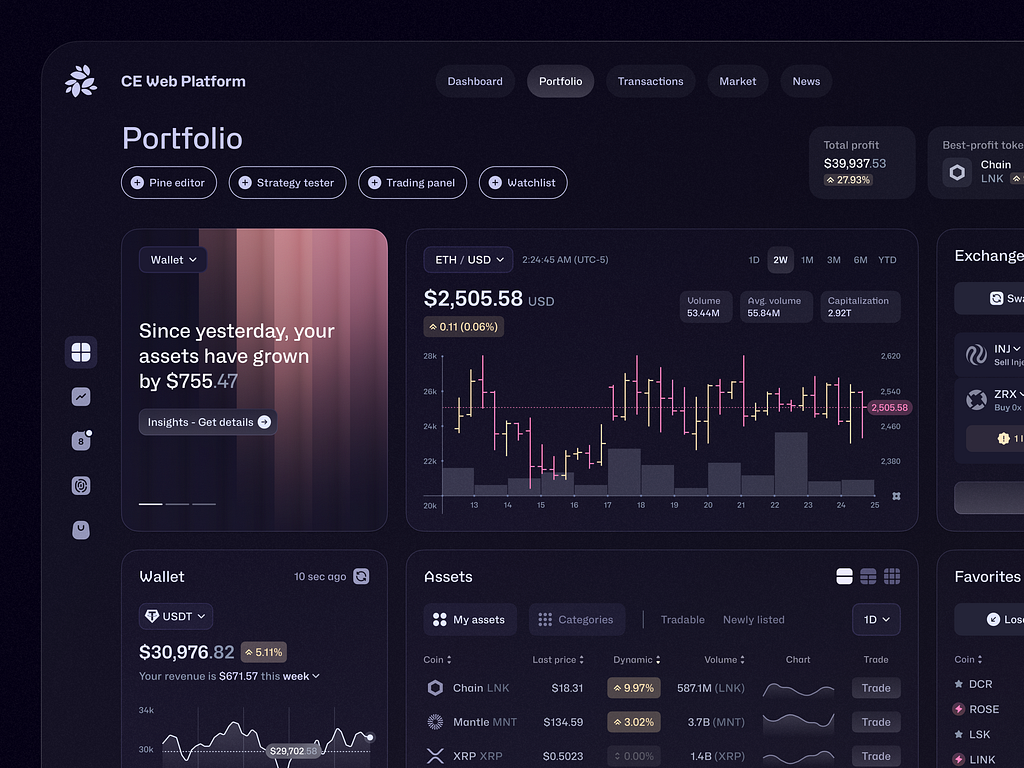

Strategic Thinking

- Business Model Analysis: As a designer, understanding the business model of your client or organization can help you make your design proposals more direct and accurate to the needs of the business and its users, and will make you spend less time explaining the value of the design.

- Competitive Strategy: Similarly to business models, understanding what is a differentiator and what is the actual competitive strategy of your client and/or organization will give you an advantage when it comes to designing a solution that suits perfectly for them, rather than a generic design response that can be easily replicated by others.

- Market Positioning: Understanding market segments, carefully defining personas, and comprehending who are the competitors of your client/organization.

- Short-Term Wins vs. Long-Term Planning: We designers must be able to learn when to identify the potential levels of value and complexity within a product planning in order to decide either what can bring short-term value or what is more suitable for long-term planning so you can start setting the ground towards that direction in the shorter-term stages, especially if you're working in an Agile environment.

Operational Excellence

- Design Ops: Everything that empowers your operations as a designer, either internally (portfolio management, digital resources, pricing structures) or externally (networking, productivity tools, invoicing, assets handoff, client communications, etc.), is something that it's worth investing time and resources into.

- Process Efficiency: Getting into an MBA helped me understand that efficiency is the main driver of the activities of an organization, and so it is for you as a designer. It is important for us designers to keep an eye on our process (and our organization's) in order to keep it as efficient, fast, and reliable as possible, either by continuously improving our skills, adopting the best tools for our work, enhancing the communication across our teams, and so on.

- Across-Team Communication: Communication is part of operational excellence since the quality of communication can either speed up or slow down the entire process of a project. Designers must constantly work on our written and spoken communication and be able to speak the same language with stakeholders, product administrators, developers, and fellow designers as well. Also, having proper and structured communication channels to document our work for the rest of an organization is crucial, for example: wikis, design tokens, design systems, style guides, manuals, etc.

Creating a Hybrid Advantage

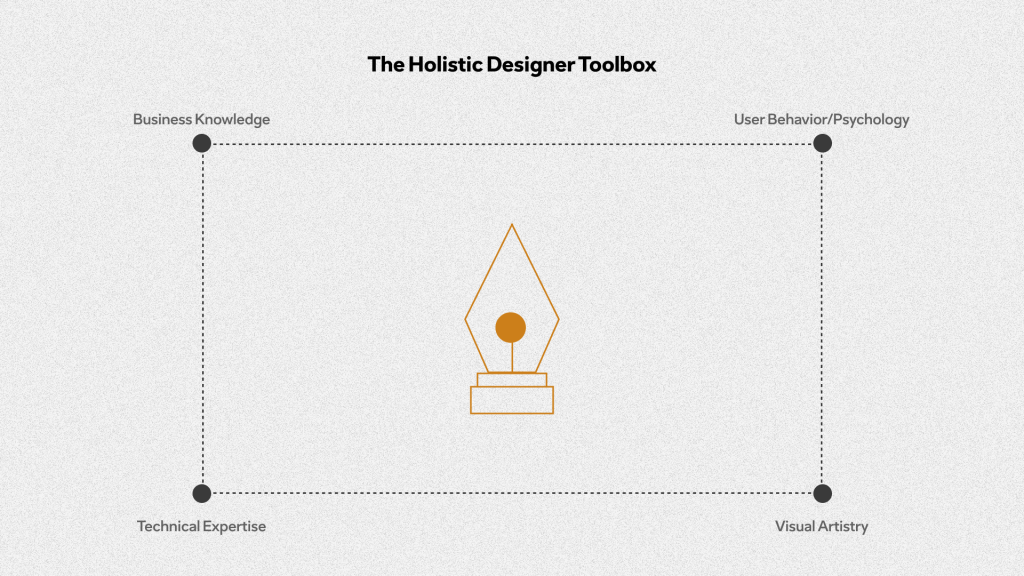

Nowadays, the role of a designer has become somewhat blurry; what the 'UX Designer' role description may look like for one organization can be completely different for another, and that role often has a seat at the strategic table of organizations, meaning that designers need more than ever to speak the business language and possess cross-level skills such as quantifying design impact, driving communication with stakeholders, comprehending business constraints, managing resources, and more.

This doesn't mean that all designers should break their heads pursuing an MBA degree for two years in order to obtain these skills. Many designers are more intuitive and obtain these skills by getting their hands on actual projects, others might prefer to stay aside and focus on more specific areas of design rather than covering the whole umbrella, and so on, but in fact, getting familiar with the subjects mentioned here will definitely give you an advantage as a designer and help you feel more confident when sitting at the strategic table, and have better communication and operational processes with your teammates.

Today I have completed about 90% of my MBA degree, and I think that getting into this decision has provided me with a more unique perspective towards design and given me lots of personal fulfillment. If you're like me and you're considering following a similar path, my advice is to first of all, have a clear plan in advance (where do you want to lead your career to, where do you see yourself in 10 years, etc.), and secondly, keep your mind open to new knowledge. Don't let it overwhelm you or intimidate you; the process can be tough in the beginning, but it will pay off when you start seeing the changes in your brain and in your tangible results as a designer.